Introduction

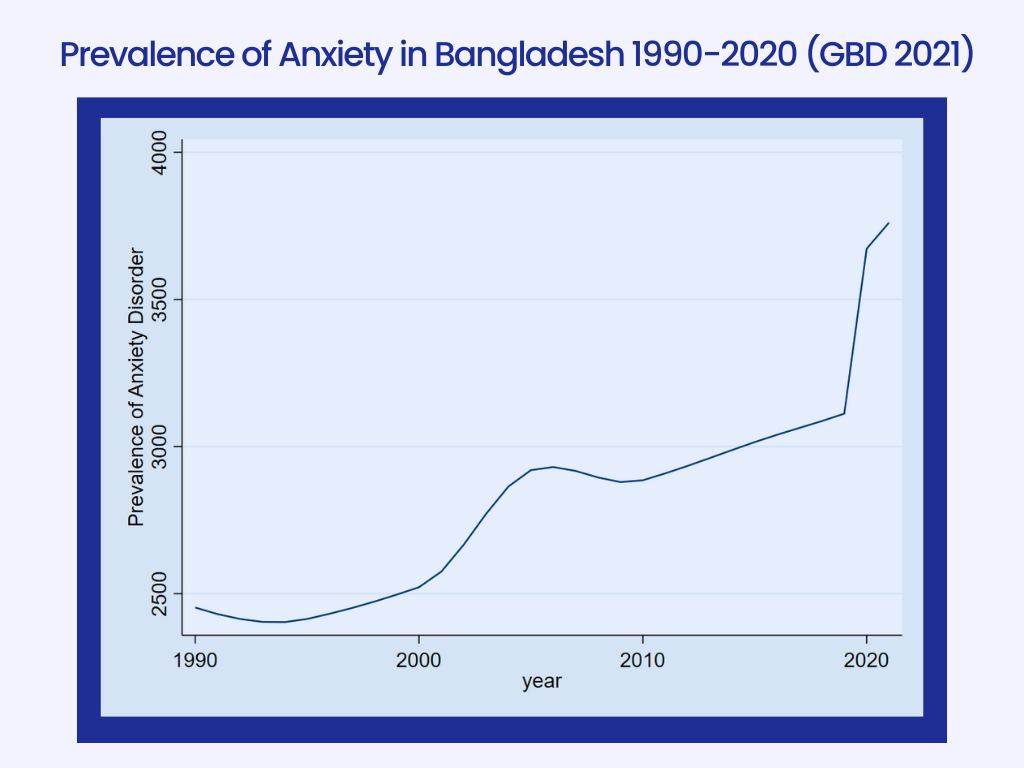

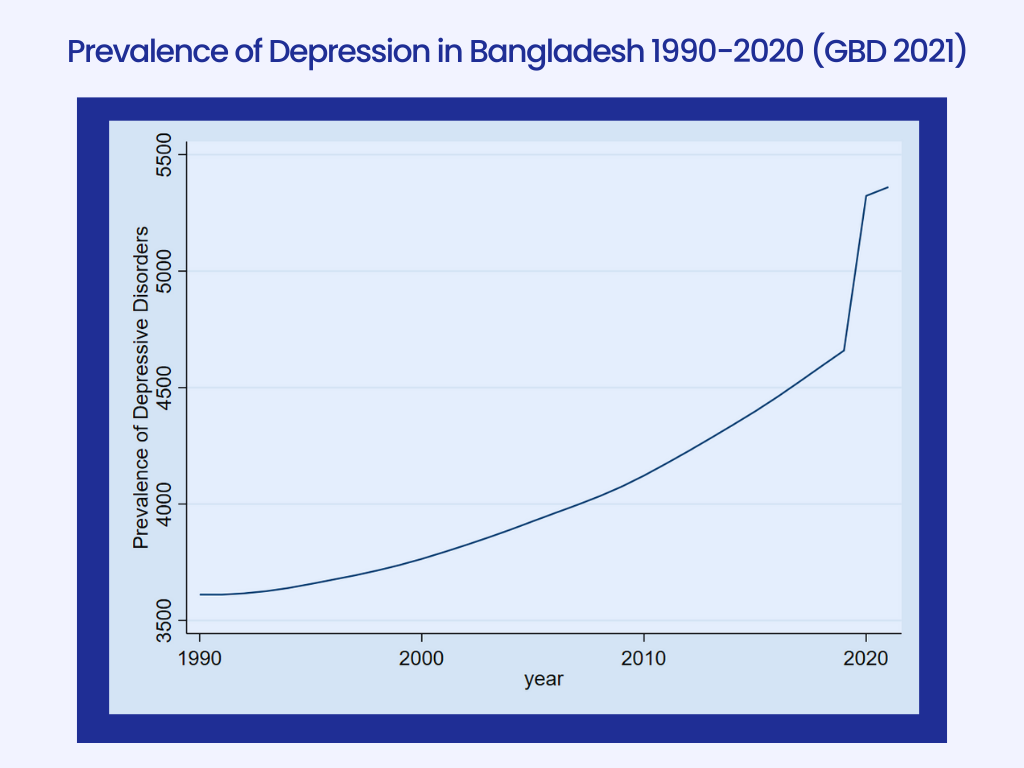

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental health is defined as “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community” (WHO, 2022). Good mental health is a prerequisite for achieving overall health and well-being. Mental health experiences vary from person to person, as individuals respond differently to life’s challenges. A person’s mental state is influenced by a range of individual, social, and structural determinants. Adverse social and economic conditions, substance abuse, and harsh parenting practices, among other factors, can significantly increase the risk of developing mental health issues (WHO, 2022). The World Health Organization (WHO) explains that depressive disorders are among the leading causes of disability worldwide, whereas anxiety disorders are some of the most common mental diseases, and they most often go hand in hand with depression (WHO, 2023). They are responsible for an enormous disease burden worldwide, affecting more than 500 million people globally (GBD 2021 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022). In recent years, global discussions around mental health have intensified, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated mental health challenges across all sectors of society. Initial estimates indicate a 26% increase in anxiety disorders and a 28% increase in major depressive disorders within just one year of the pandemic (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2019).

Image 4 and 5 go here (from drive)

More than 75% of people in low- and middle-income countries do not receive treatment for mental problems, despite the fact that there are proven, efficient treatments for them (Evans-Lacko et al., 2017). The treatment gap is wide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where up to 85% of those with mental disorders receive no treatment at all (WHO, 2021).In contrast to the 16.1% prevalence of mental illness recorded in the first National Mental Health Survey 2003–2005, roughly 19% of adults suffer from mental health disorders, according to the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare’s most recent National Mental Health Survey 2019 (Hossain et al., 2021). The increase in mental health illnesses is linked to demographic and lifestyle changes as well as rapid urbanization. The national budget of Bangladesh for the health sector was approximately US$ 2.3 billion, of which only 0.44% was allocated for mental health, mainly to spend through tertiary mental health hospitals (35.59% of allocation).There is also a chronic shortage of mental health workforce at all service delivery levels. There are 1.17 mental health workers per 100,000 population, most of whom worked at a tertiary care setup situated in large cities (National Mental Health Strategic Plan 2020–2030). In Bangladesh, mental health remains a relatively underexplored area, with even less attention given to men’s mental health. This policy brief examines the current state of mental health in Bangladesh, highlights existing gaps, and provides actionable recommendations for addressing the specific mental health needs of men.

Men’s mental health : Global and Regional Landscape

According to recent studies, over 17% of adults and 14% of children in Bangladesh suffer from poor mental health. Despite the prevalence of these issues, the majority of individuals (about 92%) who are impacted have not sought medical treatment. The proportion is considerably higher for youngsters (just 5% receive assistance). The 2019 prevalence data show an increase compared to previous research from 2005 (Faruk & Hasan, 2022). An analysis of the burden of 12 mental health disorders in 204 countries showed that mental disorders remained among the top ten leading causes of burden worldwide, with no evidence of global reduction in the burden since 1990 (Charlson et al., 2022). At a global level, over 300 million people are estimated to suffer from major depressive disorders, equivalent to 4.4% of the world’s population (Ferrari et al., 2013). Lost productivity alone for depression and anxiety has been estimated to cost the global economy US$ 1 trillion per year and is forecast to reach $16 trillion by 2030 (Chisholm et al., 2020).

Prolonged and untreated mental health issues can worsen over time, increasing the likelihood of suicide behaviour. Addressing suicide necessitates a detailed understanding of how different social groupings perceive psychological pain. Men, in particular, may experience silent conflicts determined by social conventions and internalised pressure. According to Demir (2018), men committed 72.5% of all reported suicides, illustrating the serious mental health issues that this population group faces. Men’s mental health remains an under explored and socially neglected issue in Bangladesh. The National Mental Health Survey (2019) shows 17% of adults in Bangladesh suffer from mental disorders. According to a report published in the Daily Kalbela on March 19, 2025, a study (Priory, 2024) found that 4 out of every 10 men have never spoken about their mental health. Additionally, 29% of men said that talking about mental health is embarrassing for them (Priory, 2024). About 20% avoid discussing their emotional well being due to negative stigma (Priory, 2024). Furthermore, 17% of men do not acknowledge the need for help and 16% believe that speaking about such issues would make them appear weak (Priory, 2024).

Image 1 (from drive)

However, it has been observed that 1 in every 8 men exhibits symptoms of various mental health risks (Priory, 2024). This reluctance to talk about their mental health and the surrounding social stigma contribute to increased mental health risks for men. Despite some progress in mental health advocacy, prevailing social norms label emotional vulnerability in men as weakness, discouraging them from seeking help. Moreover, the Mental Health Act 2018 lacks explicit attention to gender specific needs, leaving young men particularly students and unemployed youth vulnerable to untreated mental illness.

Image 2 (from drive)

Approximately 69.20 percent of suicides in Bangladesh were committed by men (E. Ali, 2014), yet most interventions and legal texts remain gender-neutral, overlooking distinct male psychological burdens. Traditional expectations of masculinity often result in emotional suppression, delayed help-seeking, and higher stress accumulation among men.

Key Mental Health Issues Among Men in Bangladesh

Traditional expectations of masculinity often lead to emotional suppression, delayed help-seeking, and the accumulation of unaddressed stress among men. Mental health challenges in men are frequently underreported or misunderstood due to stigma, rigid gender norms, and a lack of tailored services. Depression is a major concern, but men tend to express it differently—often through irritability, anger, risk-taking behaviors, or substance use—which makes diagnosis more difficult (WHO, 2021). Anxiety disorders are also common, yet many men suppress or deny symptoms, leading to chronic stress and related health problems (APA, 2020). Substance use disorders are significantly more prevalent in men, often serving as coping mechanisms for unresolved emotional pain (SAMHSA, 2020). Alarmingly, men are nearly twice as likely to die by suicide compared to women, often due to the use of more lethal methods and a reluctance to seek help (WHO, 2019). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) affects men exposed to violence, trauma, or accidents, resulting in emotional numbness, hypervigilance, and strained relationships (APA, 2021). Work-related stress and burnout are also pressing concerns, as societal pressure to be the sole provider increases emotional exhaustion (Harvard Business Review, 2020).

Emerging issues like muscle dysmorphia and body image concerns are growing among younger men, leading to harmful behaviors such as over-exercising or steroid use (NEDA, 2021). Loneliness and social isolation further exacerbate mental health struggles, as men are less likely to form emotionally supportive friendships (Movember Foundation, 2020). Cultural expectations around emotional suppression contribute to aggression, relationship conflicts, and, in some cases, domestic violence. Additionally, early-onset psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, often go untreated in men due to stigma and limited early intervention services (NIMH, 2020). These challenges are magnified in low- and middle-income countries like Bangladesh, where rural mental health services are scarce and traditional masculinity norms discourage emotional openness (DGHS, 2020). Addressing men’s mental health requires early intervention, culturally sensitive approaches, and a societal shift toward healthier, more inclusive definitions of masculinity.

Underlying Causes

Men’s mental health challenges are driven by a complex mix of social, psychological, cultural, and biological factors:

- Traditional gender norms teach men to suppress emotions, contributing to emotional repression and avoidance of help-seeking (Mahalik et al., 2003).

- Stigma around mental illness remains a major barrier, as expressing vulnerability is often perceived as weakness (Corrigan & Watson, 2002).

- Societal expectations of being the sole financial provider increase stress, particularly during unemployment, relationship breakdowns, or economic crises (Rochlen et al., 2010; Cleary, 2012).

- Limited emotionally supportive relationships contribute to social isolation and loneliness (Seidler et al., 2016).

- Many men turn to substance use instead of emotional disclosure, worsening their mental health (Galdas et al., 2005).

- Biological factors may also play a role, as men are more likely to externalize distress through anger or risk-taking (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012).

- In Bangladesh, these issues are intensified by rural-urban health disparities, scarce mental health services, and cultural taboos surrounding male vulnerability (NIMH, 2020).

Mental Health Policies in Bangladesh and International Best Practices

Bangladesh has made progress in mental health policy, but significant gaps remain, particularly regarding men’s mental health. Key national policies include:

- Mental Health Act 2018 – Replaced the 1912 Lunacy Act to safeguard the rights of people with mental health conditions and regulate mental health services (MoHFW, 2018).

- National Health Policy 2011 – Adopts a life-course approach to health and equity, with a focus on marginalized populations, including mental health considerations.

- National Rural Development Policy 2001 – Emphasizes rural health services and poverty alleviation, both linked to mental well-being.

- National Mental Health Policy 2019 and Strategic Plan 2020–2025 – Provide frameworks for a holistic, multisectoral approach to mental health. However, both remain largely unimplemented.

Limitations of Current Policies

Despite these policies, critical gaps remain:

- The Mental Health Act 2018, while progressive, lacks a gender-sensitive lens. It does not account for the specific mental health needs of men or recognize how masculinity-based stigma prevents help-seeking.

- The Act overlooks the unique challenges faced by rural and working men, such as long work hours, time constraints, and service inaccessibility (Khan et al., 2021).

- There is no provision for community-based or preventive interventions, such as support groups or public education programs.

- Workplace-based mental health strategies and awareness campaigns targeting men are absent, despite being internationally recognized as best practice.

- The Mental Health Act 2018 fails to promote or regulate digital mental health solutions, which are critical for reaching underserved populations, especially in rural areas. There are no clear guidelines on how individuals with severe mental health conditions can access care through digital platforms, nor provisions for monitoring, quality control, or regulation of these services. This leaves a significant policy gap in an era where technology could play a transformative role in expanding mental health access.

International Best Practices

Several countries offer models that Bangladesh could adapt:

- Australia: Victoria’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022, alongside initiatives like Beyond Blue and Man Therapy, uses male-friendly language, online tools, and confidential services to encourage men to seek help (Victorian Parliament, 2022; Beyond Blue, 2022; Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, 2022).

- In the United Kingdom, a number of focused projects have been developed to enhance men’s mental health and lower suicide rates. The NHS Long Term Plan allocates £57 million for suicide prevention and bereavement assistance in all local areas by 2023-24, with an emphasis on high-risk populations including middle-aged males (Department of Health and Social Care; NHS England, 2023-24). Independent charities, such as CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably), have reinforced these efforts by offering a free, confidential helpline and launching nationwide campaigns. In 2023-24, CALM’s helpline assisted around 167,000 people in the United Kingdom [Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM). (2024). Annual Report 2023/24]. These projects collaborate to encourage men to seek assistance, provide peer support, and combat mental health stigma through media and community outreach (Department of Health and Social Care & NHS England, 2023. Suicide Prevention Strategy for England: 2023 to 2028. UK Government).

- Canada: Provincial programs in Ontario incorporate emotional literacy, resilience training, and early intervention for boys in schools to address toxic masculinity from a young age (Oliffe et al., 2011).

Key Challenges

- Lack of Gender-Specific Focus: Existing mental health policies do not adequately address the unique needs of men, particularly male youth, students, and unemployed men.

- Urban-Centric Services: Mental health funding remains low, and services are largely concentrated in urban areas, limiting access for men in rural and underserved communities.

- High Cost of Care: Therapy and counseling are often expensive and inaccessible, especially for working-class and rural men.

- Underutilization of Digital Solutions: Digital mental health tools are not widely integrated into public health services, despite their potential to reach men who may avoid traditional care settings.

- Regulatory Gaps: There is a lack of clear policies to govern digital mental health platforms, creating challenges for quality control, privacy, and equitable access.

- Limited Family and School Engagement: Boys’ emotional literacy and well-being are not prioritized within family structures or school curricula, missing critical opportunities for early intervention.

- Masculinity-Driven Stigma: Rigid masculine norms discourage men from seeking help, resulting in untreated mental health issues and delayed care.

Policy Recommendations :

Policy Recommendations

- Reform the Mental Health Act 2018 with Gender-Sensitive Provisions

The Mental Health Act 2018 should be reviewed and reformed to explicitly incorporate gender-sensitive measures that address men’s unique mental health challenges. The current legislation does not adequately consider the impact of social stigma, patriarchal norms, and specific barriers to service access that disproportionately affect men. A revised Act should mandate the collection of gender-disaggregated data, ensure the availability of confidential, community-based mental health services for men, and include directives for public awareness campaigns aimed at challenging harmful masculine stereotypes. Drawing on best practices from the UK and Australia, such reforms would make mental health governance in Bangladesh more inclusive, equitable, and effective. - Integrate Mental Health Education into the National Curriculum

The Ministry of Education should introduce age-appropriate, culturally sensitive, and evidence-based mental health modules into the national school curriculum. Particular focus should be given to emotional literacy, stress management, and resilience training for boys at the secondary level. Teachers must receive professional development and capacity-building training to deliver these lessons effectively and sensitively. This initiative could be modeled after Canada’s school-based mental health programs, which have successfully dismantled toxic masculinity and normalized emotional expression among male students. Early intervention in schools will help reduce long-term psychological distress and improve emotional intelligence in future generations of men. All interventions should be co-designed with male students and educators to ensure relevance and impact. - Develop a National Digital Mental Health Platform for Men

The Government of Bangladesh, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and private sector partners, should develop a national digital mental health platform specifically tailored to the needs of men. This platform should offer anonymous, confidential access to licensed mental health professionals via chat, voice, or video-based counseling. The interface must use male-friendly language and content designed to deconstruct harmful masculine norms while promoting help-seeking behavior. Inspired by Australia’s Beyond Blue and Man Therapy, the platform should include self-assessment tools, psychoeducation resources, and emergency response mechanisms. Targeted outreach must prioritize working-class and rural men, who are often underserved in conventional mental health systems. Special initiatives should also address the mental health needs of men with disabilities, ensuring no group is left behind.

Conclusion

Men in Bangladesh, particularly youth and students, urgently need targeted psychosocial, legal, economic, and digital interventions to support their mental well-being. Addressing this requires a multi-faceted approach: reforming the Mental Health Act to ensure inclusivity and protection, making mental health services more affordable and accessible, integrating school-based and family-centered support systems, and leveraging technology for early intervention and outreach. Together, these actions can shift the focus from crisis management to proactive care, creating a system that empowers men to maintain their mental health and thrive in all areas of life.

References :

Demir, B. (2018). Male suicide and the overlooked mental health crisis. Journal of Public Health Studies, 45(3), 211–225.

- Ali (2014). Epidemiological analysis of suicide in Bangladesh: A gendered perspective. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60(2), 157–164.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2018). Mental Health Act, 2018. Official Gazette and Legal Copy (Government of Bangladesh, Ministry of Health) http://bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd/act-details-1262.html (Or available via https://mohfw.gov.bd → “Laws & Policies” section)

National Mental Health Survey of Bangladesh 2018–19 (NMHS). Conducted by: National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) https://nimh.gov.bd/reports/national-mental-health-survey-2018-19

World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Suicide worldwide in 2022: Global health estimates. Published by: World Health Organization https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240069919

He Ara Oranga (2018). Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction. Official Report: Government of New Zealand https://www.mentalhealth.inquiry.govt.nz/inquiry-report/he-ara-oranga/

Australian Government Department of Health. (2020). National Men’s Health Strategy 2020–2030. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-mens-health-strategy-2020-2030

UK Department of Health and Social Care. (2021). Reforming the Mental Health Act: White Paper. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/reforming-the-mental-health-act

Health, N. L. G. (2020). Mental health matters. The Lancet Global Health, 8(11), e1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30432-0

Ferrari, A. J., Charlson, F. J., Norman, R. E., Flaxman, A. D., Patten, S. B., Vos, T., & Whiteford, H. A. (2013). The Epidemiological Modelling of Major Depressive Disorder: Application for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS ONE, 8(7), e69637. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069637

Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. (2022). The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(21)00395-3

World Health Organization: WHO. (2022, June 17). Mental health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx), https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results

National Mental Health Strategic Plan 2020-2030. (2020). In স্বাস্থ্য অধিদপ্তর, স্বাস্থ্য সেবা বিভাগ, স্বাস্থ্য ও পরিবার কল্যাণ মন্ত্রণালয়. Government of The People’s Republic of Bangladesh. https://dghs.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/dghs.portal.gov.bd/notices/fc97a57f_cdc1_4584_9125_5ff6a07f5b74/2023-05-21-08-42-0ed7c90487c5d7c65b9913ecb278f765.pdf

National Health Policy 2011. Dhaka: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2011 http://www.mohfw.gov.bd/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=74&Itemid

Priory. (2024). Men and Mental Health: A National Study on Stigma, Silence and Suffering. The Priory Group.

National Rural Development Policy. Dhaka: Rural Development and Cooperatives Division; 2001 (https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5b2b99af4.pdf,

Australian Government. (2022). National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement. https://www.health.gov.au

Ballinger, M. L., Talbot, L. A., & Verrinder, G. K. (2009). More than a place to do woodwork: A case study of a community-based Men’s Shed. Journal of Men’s Health, 6(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jomh.2008.09.006

Beyond Blue. (2023). Men’s mental health in Australia. https://www.beyondblue.org.au

Canterbury District Health Board. (2015). All Right? Campaign evaluation report. Christchurch, NZ.

Department of Health and Social Care. (2021). Reforming the Mental Health Act. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk

Mind UK. (2022). Men’s mental health: Key facts and figures. https://www.mind.org.uk

Oliffe, J. L., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Bottorff, J. L., Johnson, J. L., & Hoyak, K. (2011). “You feel like you can’t live anymore”: Suicide from the perspectives of Canadian men who experience depression. Social Science & Medicine, 73(5), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.017

Australian Government. (2022). National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement. https://www.health.gov.au

Ballinger, M. L., Talbot, L. A., & Verrinder, G. K. (2009). More than a place to do woodwork: A case study of a community-based Men’s Shed. Journal of Men’s Health, 6(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jomh.2008.09.006

Beyond Blue. (2023). Men’s mental health in Australia. https://www.beyondblue.org.au

Canterbury District Health Board. (2015). All Right? Campaign evaluation report. Christchurch, NZ.

Department of Health and Social Care. (2021). Reforming the Mental Health Act. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk

Mind UK. (2022). Men’s mental health: Key facts and figures. https://www.mind.org.uk

Oliffe, J. L., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Bottorff, J. L., Johnson, J. L., & Hoyak, K. (2011). “You feel like you can’t live anymore”: Suicide from the perspectives of Canadian men who experience depression. Social Science & Medicine, 73(5), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.017

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2018). Mental Health Act, 2018 (Act No. 47 of 2018). Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

Mahalik, J. R., Burns, S. M., & Syzdek, M. (2003). Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men’s health behaviors. Social Science & Medicine, 64(11), 2201–2209.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 161–187.

Seidler, Z. E., Dawes, A. J., Rice, S. M., Oliffe, J. L., & Dhillon, H. M. (2016). The role of masculinity in men’s help-seeking for depression: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 106–118.

Khan, M. M. H., Chowdhury, N. F., & Rahman, M. (2021). Barriers to implementation of the Mental Health Act 2018 in Bangladesh: A critical review. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 24(3), 151–158.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Anxiety and men: Why men may struggle in silence. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/report

American Psychological Association. (2021). PTSD in men. https://www.apa.org/topics/ptsd

Directorate General of Health Services. (2020). National Mental Health Survey of Bangladesh 2019-2020. Government of Bangladesh.

Harvard Business Review. (2020). What causes burnout and how to overcome it. https://hbr.org/2020/12/what-causes-burnout

Movember Foundation. (2020). Mental health and social connection. https://uk.movember.com/story/view/id/12518

National Eating Disorders Association. (2021). Muscle dysmorphia. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/learn/by-eating-disorder/other/muscle-dysmorphia

National Institute of Mental Health. (2020). Schizophrenia. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). Behavioral health barometer: United States, volume 6. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

World Health Organization. (2019). Suicide worldwide in 2019: Global health estimates. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643

World Health Organization. (2021). Mental health: Strengthening our response. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

Cleary, A. (2012). Suicidal action, emotional expression, and the performance of masculinities. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 498–505.

Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2002). Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry, 1(1), 16–20.

Galdas, P. M., Cheater, F., & Marshall, P. (2005). Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 616–623.

Mahalik, J. R., Burns, S. M., & Syzdek, M. (2003). Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men’s health behaviors. Social Science & Medicine, 64(11), 2201–2209.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2020). National Mental Health Survey of Bangladesh 2019–2020.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 161–187.

Rochlen, A. B., McKelley, R. A., & Pituch, K. A. (2010). A preliminary examination of the “Real Men. Real Depression” campaign. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 11(1), 1–13.

Seidler, Z. E., Dawes, A. J., Rice, S. M., Oliffe, J. L., & Dhillon, H. M. (2016). The role of masculinity in men’s help-seeking for depression: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 106–118.

Beyond Blue. (2022, July). Man Therapy campaign overview. Beyond Blue Ltd., supported by the Australian Government Department of Health. Australia. https://www.beyondblue.org.au/about-us/about-our-work/initiatives/man-therapy

Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM). (2024, March). Annual report 2023/24. The CALMzone, United Kingdom. https://www.thecalmzone.net/about-calm/what-is-calm/annual-reports/

Department of Health and Social Care, & NHS England. (2023, September 11). Suicide prevention strategy for England: 2023 to 2028. HM Government, United Kingdom. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/suicide-prevention-strategy-for-england-2023-to-2028

Gillham, C., & MacLean, S. N. (2023). Guys Work: Addressing toxic masculinity through school-based interventions for adolescent boys. Psychology in the Schools.

Kutcher, S., & Wei, Y. (2014). Mental Health & High School Curriculum Guide (Version 2014). Canadian Mental Health Association & TeenMentalHealth.Org.

Faruk MdO, Hasan MT. Mental health of indigenous people: is Bangladesh paying enough attention? BJPsych International. 2022;19(4):92-95. doi:10.1192/bji.2022.5

Evans-Lacko S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders:

results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol Med. 2018;48(9):1560-1571.