Written by – Mahepara Z Ahmed

As the pandemic wears on and we adapt more and more with the sudden and continuous changes in our lives, we can not help but pay attention to the rather unspoken aspect of our health, mental health.

Now mental health disorders are not something that emerged with the pandemic but there was a certain aspect of this pandemic that opened a door for all of us, who in general don’t take out much time to think about it, to think how mental health works, that is, the dreadful isolation and lockdown that seemed always imminent to disrupt the lifestyle we are accustomed to. For people who didn’t quite understand or refused to understand the importance of mental health understood how intimately mental health is related to our daily pursuits, in order for them to be conducted properly if not perfectly.

Population at risk

Now we can clearly see in hindsight that the population at risk were young adults/adolescents. People belonging to that age group reported disorders such as anxiety, depression and substance abuse. 1 out of every 7 adolescents now has a mental disorder, and suicide is now the fourth leading cause of death among 15-19 years old, which became more pronounced during the year 2020. If we want to look for the cause behind why this particular age group was affected more, we need to shed light on the fact that the closure of universities, schools, and colleges was unpredictable even a year prior to the pandemic. But as Dr. Tasdik Dip, Global Mental Health Researcher and YPF Fellow, stated,

“We didn’t address the problem as strongly as we should have.”

The pandemic followed by the economic recession, job loss added more people to the list experiencing mental health issues. Adults in households with job loss or lower incomes report higher rates of symptoms of mental illness than those without job or income loss. Globally 53 million cases of major depressive disorders, and 76 million cases of anxiety disorders were added due to the pandemic, among which women and younger people were the primary victims.

-

- Why women? Since women, especially mothers, faced problems with school closures and lack of childcare. Also in this region, women are expected to take the household workload, whether the men are present in the family or not. Also women’s medical conditions in general are much less likely to be reported, and less recognized and managed effectively.

Mental Health Status in our country

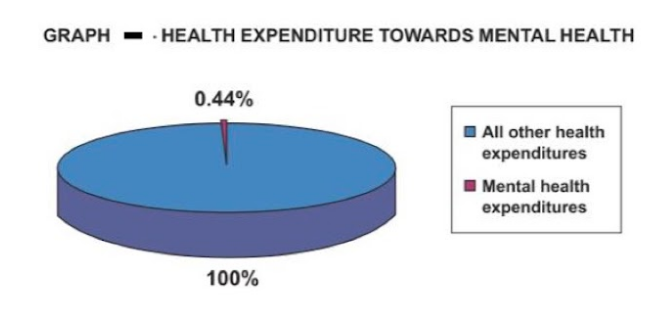

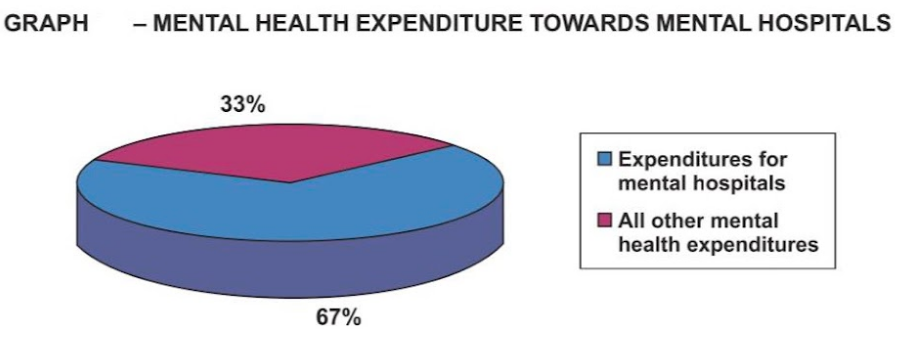

Out of the entire Bangladeshi population, 4% of people suffer from depression. This statistic trails just around 2% behind the world’s most depressed country, Ukraine, with 6.3% of its population suffering from depression. An estimated 10,000 Bangladeshi people die by suicide annually. The government, with the assistance of many Non-governmental organizations, is taking positive action to address mental health in Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, there are only 270 psychiatrists and roughly 500 psychologists serving a population of more than 166 million. This equates to 216,000 people per specialist. Most mental health professionals are located in urban areas so people in rural areas have limited access to mental health services. Furthermore, the country’s sole government-run mental hospital has only 500 beds. Mental health also has limited funding. Only 0.44% of the government health budget is allocated to the mental health sector.

Solution and the obstacles to the solution

Now, coming to the solution, what is the solution to this wide range of problems? Seeking clinical help will be the first and foremost thing. Then comes the personal and social aspect of the solution. But when asked to different individuals struggling with different mental problems, they stated different obstacles they faced while seeking help. For them, the thing they found hard was the expense of seeking help from a therapist or psychiatrist. Since talking about mental health problems is not accepted with open arms yet, some found it difficult as well. Moreover, Lack of trained and empathetic professionals, people not knowing when to go to a therapist and when to go to a psychiatrist , religious bias, sexism,lack of accountability of the professional, lack of regulation are few factors that contribute more to the obstacles of the solution.

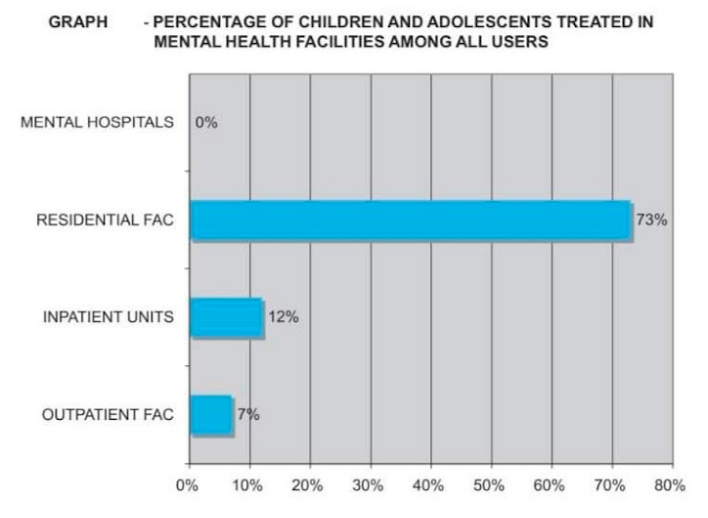

On top of that, few rarely know or acknowledge the effect of the environment on mental health, for instance, how noise pollution can be one of the factors behind irritability, how these environmental stressors can take a toll on mental health. Not talking about these are one of the major social barriers and there are other structural barriers which arise when one goes to seek help from the professionals, as few professionals find this unnecessary to provide mental healthcare to the adolescents.

“I have been denied professional help because I was not accompanied by my parents.”said an individual when asked what kind of difficulties they face while going for help to the professionals. How can this be resolved? Can there be a policy to make it go away? Or do we need to focus on something else to make it go away? We cannot but admit that, “Investing in adolescent health could be the most wise and sustainable investment for us.”

In an article published during the 70s, in a post-liberation war state of the country, it said that a person being male, rich, educated and residing in the urban area will have more access to healthcare than a person who doesn’t fall into those four groups. On this Dr. Tasdik Dip mentioned that we haven’t progressed much from that state of the healthcare system, that we are still stuck in that phase.

Intersecting the four groups who have the privilege to get help, for a person not falling into any of those four groups, do we have any policy at all to help them?

Measures taken in our country

In our country, what do we have to combat these altogether? In the year 2018, Bangladesh passed a new Mental Health Act, replacing the old Lunacy Act 1912. The new act brings hope for those with mental illnesses by protecting their property rights and keeping provisions for health and rehabilitative services. But it also has some loopholes that might still need some more thoughts.

First, the act has a provision of punishing medical practitioners if found guilty of providing false certificates of mental illness to anyone Which might scare or demotivate the professionals providing help. With the poor doctor-patient ratio, this might not lead us to a solution we are looking for.

Second, Bangladesh spends only 0·44% of its total health-care expenditure on mental health and no social insurance programme covers mental health services. The new act does not address this enormous economic burden of mental health care, which remains a major weakness of the act.

Third, the new act has failed to acknowledge issues such as confidentiality, accountability, and human rights aspects of mental illnesses which doesn’t resolve the problem we stated previously.

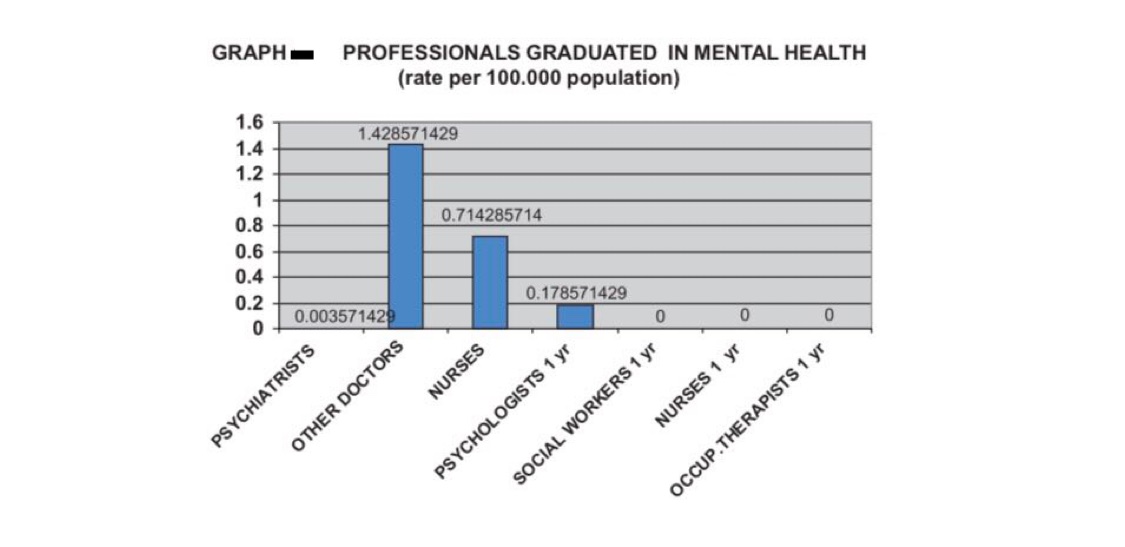

Also we need to think about the doctor-patient ratio as well. According to a study, In our country, the number of professionals graduated last year in academic and educational institutions per 100,000 is as follows: 0.0036 psychiatrists, 1.43 medical doctors (not specialized in psychiatry), 0.71 nurses (not specialized in psychiatry), 0.18 psychologists with at least 1 year training in mental health care, 0 nurses with at least 1 year training in mental health care, 0 social workers with at least 1 year training in mental health care and 0 occupational therapists with at least 1 year training in mental health care. Between 1 and 20% of psychiatrists emigrate to other countries within five years of the completion of their training.

Apart from these loopholes in the new mental act, there are few societal factors that add to the complications of the solution. For instance, a problem can be solved only when it is acknowledged. In our society, we can see public stigmas that involve discriminatory attitudes that others have about mental illness. Accessibility is also one of the hindrances. To solve this, Dr. Mahbub Hossain, Psychosocial Health Researcher, Texas A&M University suggested,

“ At every level of the system, we need to organize the service delivery in a way that is easily accessible. It can also work towards preventing the onset of major psychosocial issues in an individual.”

To connect the community and system and for bridging the gap, we can think of ways that can be helpful. As Dr Mahbub Hossain pointed out, “ Integrated mental health in primary care practice can be made accessible by telemedicine or by creating a PR team. There has been a lot of discussion about social networking based mental health support as well.”

In the end, can we ask ourselves, is budget the real problem here or the process? Or both?

References:

- https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/depression-rates-by-country

- https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/bangladesh-population/

- Alam, F., Hossain, R., Ahmed, H., Alam, M., Sarkar, M., & Halbreich, U. (2021). Stressors and mental health in Bangladesh: Current situation and future hopes. BJPsych International, 18(4), 91-94. doi:10.1192/bji.2020.57

- 4. Hossain, M. M., Hasan, M. T., Sultana, A., & Faizah, F. (2019, January 1). New Mental Health Act in Bangladesh: unfinished agendas. The Lancet Psychiatry. Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30472-3

- 5. Alam, F., Hossain, R., Ahmed, H., Alam, M., Sarkar, M., & Halbreich, U. (2021). Stressors and mental health in Bangladesh: Current situation and future hopes. BJPsych International, 18(4), 91-94. doi:10.1192/bji.2020.57

Mahepara Z Ahmed is a third year MBBS student at Armed Forces Medical College and an associate at YPF Health Policy Network.