Authors : Shoaib Mahmudul Hoque, Lamia Mohsin & Samiha Khan

Under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the international community has agreed that industrialized countries, which were the biggest beneficiaries of greenhouse gas pollution, should support climate projects in developing countries. Climate finance refers to the transfer of capital from developed to developing nations in adherence to the recommendations laid out in international agreements such as COP and Paris Agreement. According to the framework, this capital may be drawn from public or private sectors.

The money developing countries receive in climate finance is used to fund projects in mitigation, adaptation, and more and more in cross-cutting activities that combine both. Funding for adaptation builds hurricane shelters or sea walls, restores mangrove forests and wetlands etc. Mitigation projects reduce greenhouse gas emissions by shifting energy production towards sustainable sources. Examples of this include funding for clean public transport in cities; generating renewable energy from wind and solar power; or planting trees in deforested areas.

Industrialized economies have profited from carbon-intensive economic development. But this development path is no longer an option for poor countries that need to skip a few steps and go directly to using clean, renewable energy. The concept of developed nations funding the projects is only fair considering that developing countries are the most hard-hit when it comes to climate change whereas their contribution to the problem has been minuscule. This is a matter of climate justice.

A good example of this would be Bangladesh. In 2020, the country ranked 155th in terms of vulnerability and ability to adapt to the negative impact of climate change whereas the country’s contribution to global CO2 emission IS 0.000000005% compared to China. This shows how disproportionately countries are hit by climate change.

History of Climate Finance:

Climate Finance is available to developing countries in many different forms, multilateral climate finance (UNFCCC, World Bank, Asian Development Bank), bilateral climate finance (EU, Japan, Nordic countries), non-governmental climate finance (Bloomberg, ClimateWorks) and Regional Funds (Amazon Fund, Bangladesh Climate Change Trust Fund).

The 15th Conference of Parties (2009) held in Copenhagen was a significant turning point for the climate finance sector because the conference saw developed countries, at the behest of developing countries, developed countries promised to provide US$30 billion for the period 2010-2012, and to mobilize long-term finance of a further US$100 billion a year by 2020 from a variety of sources. The Paris Agreement saw developed country parties pledge to provide USD$100 billion in climate finance annually from 2020 to 2025.

As of November 2020, development banks and private finance had not reached the $100 billion. However, the world’s publicly financed development banks have pledged to tie together their efforts to rescue the global economy from the Covid-19 crisis and the climate emergency, with an emphasis on green recovery, especially for poorer countries.

Good and Bad Climate Finance:

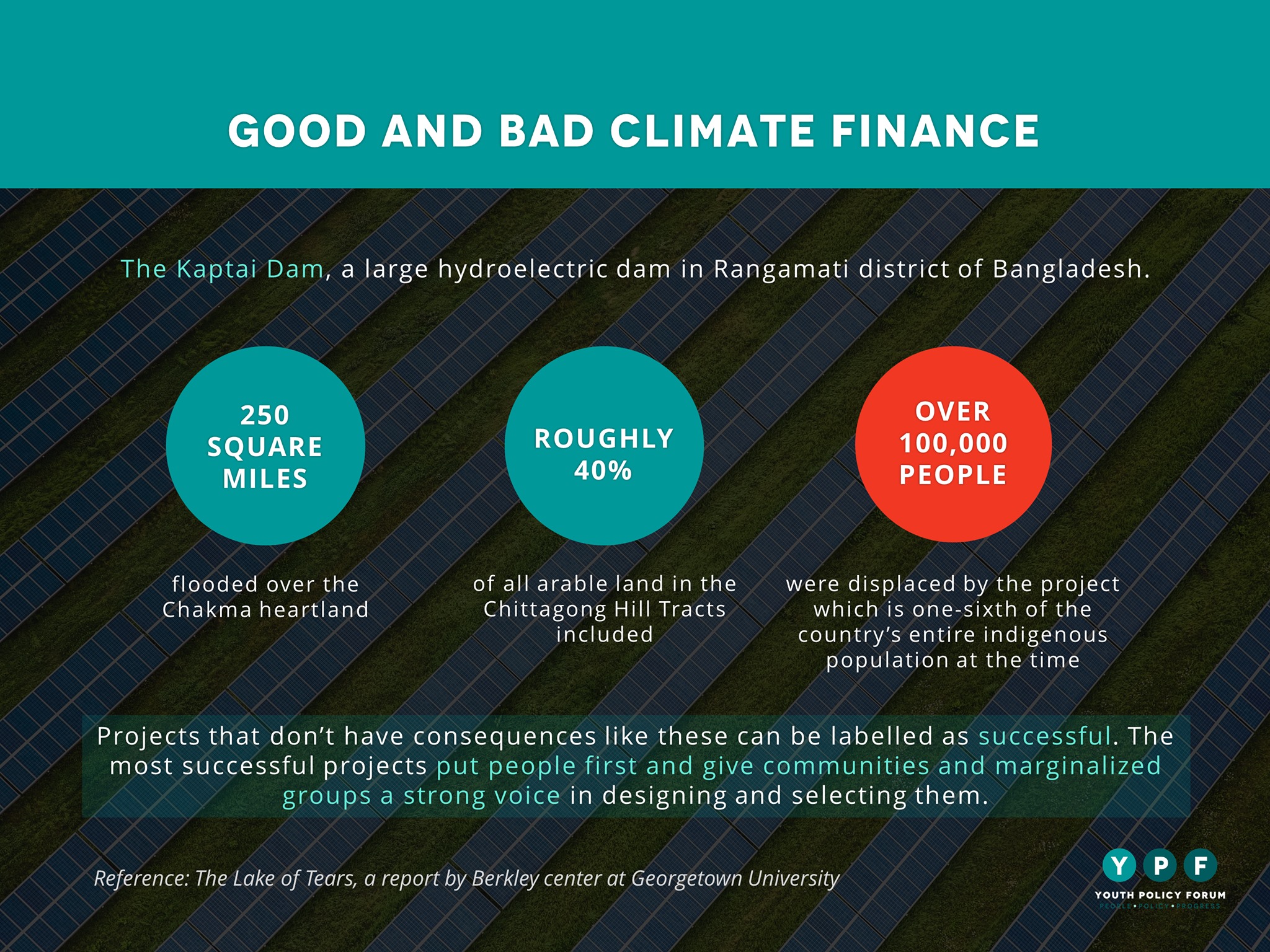

When done well, climate projects allow communities in developing countries to bear the worst effects of climate change and adjust their livelihoods for an uncertain future. However, misguided projects can easily make things worse. Large hydroelectric dams built to create renewable energy can displace people and destroy their livelihoods. The Kaptai Dam, a large hydroelectric dam in Rangamati district of Bangladesh, flooded over 250 square miles of the Chakma heartland, including roughly 40 percent of all arable land in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Over 100,000 people were displaced by the project which is one-sixth of the country’s entire indigenous population at the time. Biofuel industry can be another ideal example. Biofuel projects are aimed at reducing dependence on oil imports and slowing global warming due to fossil fuel emissions, but growing food crops for biofuel can push up food prices and create food insecurity if not done right. When farmers in South America and South-East Asia were incentivized to start growing crops for fuel in lands that were previously used for food, the regions reported massive food shortages in the following years. Projects that don’t have consequences like these can be labelled as successful. The most successful projects put people first and give communities and marginalized groups a strong voice in designing and selecting them.

While rich countries are supposed to take the lead, they are yet to reach the goal of US$100 billion. Most of the money today comes from the private sector, and governments increasingly give loans that need to be paid back. These loans place a strain on poor recipients, and investors often have priorities that do not align with the needs of communities and countries. This is why climate finance should be mostly in the form of grants.

With not enough money being available for climate projects, only the ones that do no harm to people or the environment, and ones that benefit human rights and gender equality should be funded.

Green Climate Fund: An example of Good Climate Finance

The financial transfers to fund climate projects in developing nations are often made through multilateral funds, the largest of which is the Green Climate Fund (GCF). As a new and ambitious fund, the GCF tries to learn from the past mistakes of other organizations where climate projects had harmful consequences – such as environmental degradation or human rights violations.

GCF has been operational only since 2015, yet it has funded a total of 159 projects, avoided CO2 equivalent of 1.2 billion tonnes, increased resilience of 407 billion people in developing countries and made a commitment of 7.3 billion dollars as of 2021.

The reason why GCF is so innovative is because of how they manage their internal and external activities. The Governing Board of the GCF is made up of an equal number of people from developed and developing countries – so that recipients have an equal say in funding decisions. Apart from that, to promote inclusion, their projects are gender-responsive and respect the rights of women and indigenous communities, by requiring consultations with them.

To ensure accountability, GCF has several independent units responsible for monitoring and evaluation. It also gives people in recipient countries the opportunity to make a suggestion, complain and ask for compensation if projects go wrong and cause harm. Although GCF has the potential to set an example of best practices for transformative climate finance, the fund faces a challenge of replenishment as the demand far outstrips the money available. For now, GCF aims to catalyse a flow of climate finance to invest in low-emission and climate-resilient development, driving a paradigm shift in the global response to climate change.

Climate Finance: Bangladesh status quo

The vulnerability of Bangladesh emanates mainly for its geographical locality, as the lowest riparian country of the Bay of Bengal. Despite Bangladesh’s highly dense population and resource constraints to cope with climate adversities, questions persist whether the country receives its fair share of Climate Finance (CF) compared to other least developed countries (LDCs).

Based on priority, Bangladesh is planning for the effective utilization and need-based allocation of the proposed climate budget of $2,850 million for FY 2020-21 according to a CPD study. The effective use of this budget will require a concerted effort of the government, non-government, private sector, financial and other institutes to monitor the climate budget expenditure, thereby enabling to exercise overall ownership of the concerned in the climate investment process. To that, the ‘Climate Financing for Sustainable Development: Budget Report 2020-21’ calls for the integration of 25 ministries through a programmatic approach in interventions across key thematic areas and cross-cutting issues. The latter may include social and environmental safeguarding, knowledge management, and gender mainstreaming. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have now made it possible to integrate CF quite easily into the national planning strategies.

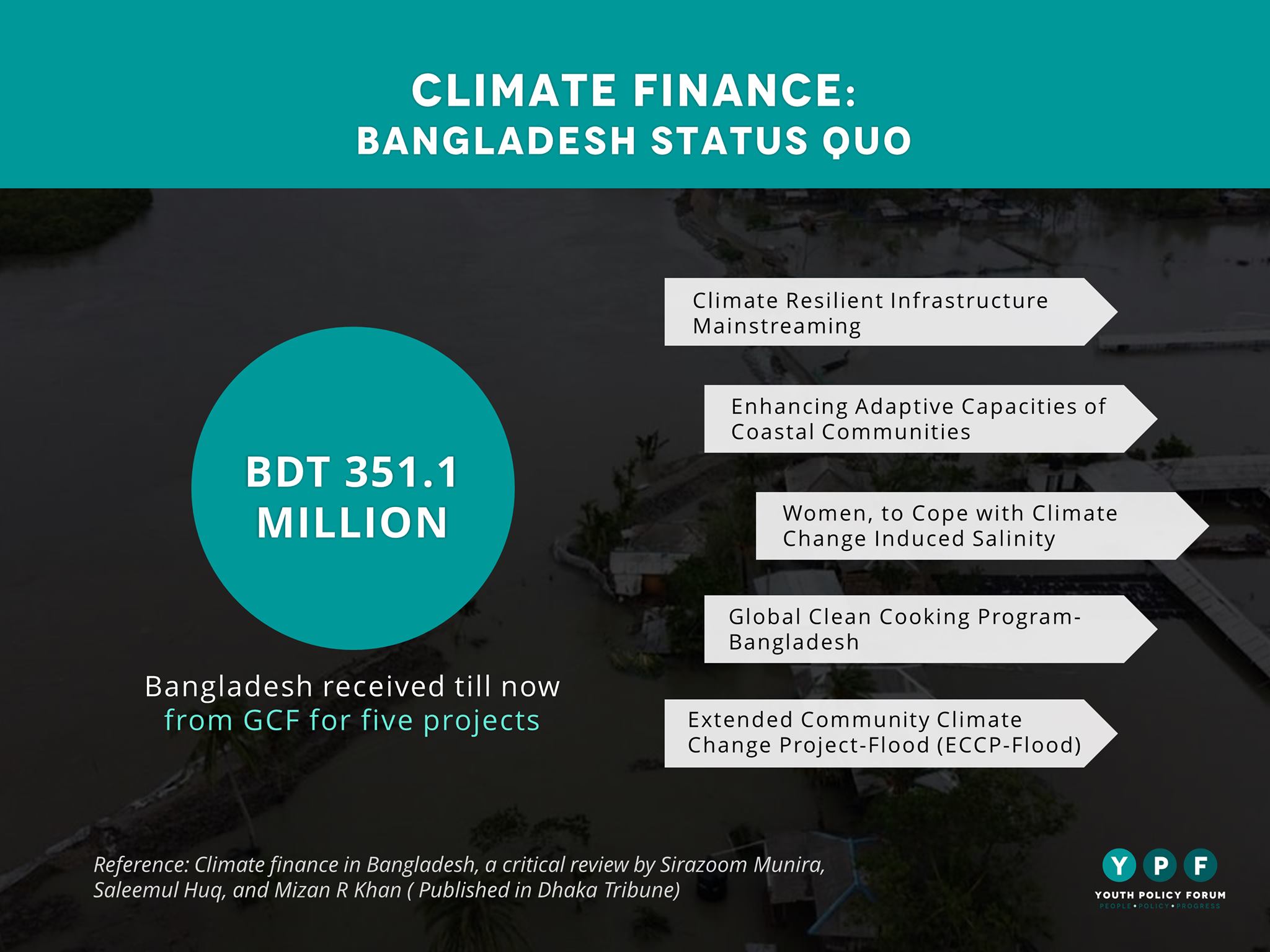

The Green Climate Fund (GCF), which is known as one of the main vehicles for channeling CF, and Bangladesh till now received Tk351.1 million from GCF for five projects, that include Climate Resilient Infrastructure Mainstreaming, Enhancing Adaptive Capacities of Coastal Communities, Especially Women, to Cope with Climate Change Induced Salinity, Global Clean Cooking Programme- Bangladesh and Extended Community Climate Change Project-Flood (ECCP-Flood).

Of this, the grant is $256.5 million which was approved in November 2020, as the first concessional credit line for Bangladesh and the first private sector financing from GCF to Bangladesh to promote private sector investment through large-scale adoption of energy-efficient technologies in textile and garments industries. However, Bangladesh as an LDC should further raise its voice to have CF as grants, especially for adaptation, as promised at Copenhagen in 2009 by the developed countries. For that, the country should continue to remain well-equipped to meet the standards set by the GCF and other adaptation fund windows.

The Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) has approved 11 projects in Bangladesh so far with a total fund of $176.66 million of funding and $1049.01 million co-financing. PPCR’s role in improving climate-resilient agriculture and food security, reliability of freshwater supply, sanitation and infrastructure, and enhancing the resilience of coastal communities in Bangladesh has been effective in creating other co-benefits. On the other hand, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) which has funded 43 projects in Bangladesh, has provided a grant total of $160 million, which generated $1,037 million as additional co-financing from other sources including from Bangladesh.

Bangladesh incurs roughly 2.5% loss of GDP each year due to natural disasters. In addition, human development progress sets back through loss of life and livelihood, with an annual average number of 13,200 deaths and millions affected. However, the country receives only about 20% of CF. Currently, it spends about $3 billion a year to address climate change. This is only one-fifth of the amount the World Bank estimates the country would need as adaptation finance by 2050.

About the Authors: Lamia Mohsin is a Junior Consultant at the UNDP and a key member of the Environment Policy Netowork at YPF, Shoaib Mahmudul Hoque is the coordinator of the Environment Policy Network, and Samiha Khan is currently working in the environment and foreign policy networks at YPF.